2. A Jeffersonian matter? Funding merit.

Dear John,

It’s taken me a while to work up a reply to your excellent post–not least because I so tragically misread your previous. I think you hit the nail on the head in asking: “who if anyone has interest in funding meritocracy these days, and how much do our cliches of critique, etc. depend on their capacity to mold the “talent” those Redbook authors think America needs? ”

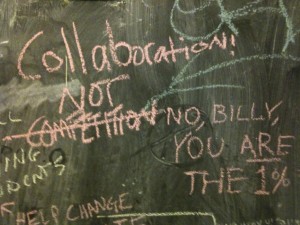

With Chris Hayes and Althusser you point out that the language of merit can ratify privilege. (For Hayes, this is because of the contradictory principles of difference and mobility inherent in meritocratic systems, for Althusser it would because, in “the last instance which never in fact arrives,” capital has structured the rules according to which merit is judged merit.) I also take the (mostly implied) point that even when we “see through” merit to the privilege it ratifies, you and I will continue to believe in meritocracy anyway, because our professional practice is inconceivable without it: we’d be different people in a different line of work. No question of getting outside this ideology, only, perhaps, of exploiting its contradictions. One answer to your question, then, is that the already “meritorious” want to fund meritocracy and that, insofar as they have the resources to do so, they may be likely to fund merit in ways that undermine meritocracy by exempting their own values and interests from challenge.

This leaves your intriguing suggestion that the 20th Century’s educational institutions may have exhausted the meritocratic rhetoric that justified them, such that “meritocracy” can no longer be appealed to as a reason for funding public universities and, more particularly, humanities disciplines. If this suggestion is correct, the exhaustion of the old order would create an opening for alternatives that would appear horrifying or lovely, depending on one’s point of view and ability to apprehend them.

In the “America needs talent” universe of the Redbook it was imagined that properly funded high schools would do the sorting, and also that the cost of college would pose no obstacle for the meritorious student. Students certified by the very best colleges could confidently claim to have obtained their credentials due to talent. With a Jacksonian general education in place, they could also claim that those credentials certified a certain kind of public virtue, an exposure to the stuff of the commonweal, particularly as rendered in classic works of fiction. Even in 1945 this was an ideal. The Redbook authors’ insist throughout on the wide disparity in the quality of high school and college experiences. If high school disparities are regarded as a problem, college disparities, as you note, are regarded as inevitable. The authors take for granted that vocational, junior, and 4-year liberal arts colleges differ (178-180) and suggest a place for general education in each before focusing on Harvard as a test case. I find no argument in the Redbook that college should be publicly funded. The argument, rather, is that Harvard should and will provide financial assistance to “broaden the economic base from which its students are drawn” (184). Clearly, others had made and would make an argument for publicly funded meritocratic universities–not least those responsible for the Morrill Act. We probably need to look more closely at some of those arguments. So long as the Redbook provides our example of mid-century rhetoric, however, it’s worth underscoring a fact that emerged via our last round of exchanges: the authors give the humanities (and especially English) a special role in Jacksonian leveling but not so much in Jeffersonian sorting. When Harpham appeals to Redbook-era clichés, he’s reprising a move barely hinted at in the Rebbook itself. That move marries the work of literary eduction to specialization in literary reading and thereby makes the role of English in “general education” depend on special expertise, talent, and sensitivity. The Redbook and “Criticism, Inc.” are not merely contemporaries, but structural complements, the role prescribed for English in general education makes no sense absent the kinds of professors Ransom (and Leavis) believe should be trained. It is this compact, established at mid-century, that the second half of the century brought to ruin. The proposition that a healthy nation needs general education that includes the humanities is alive and well. More about this in a later post. For now, at the risk of belaboring the point, I just want to underscore that the Redbook’s “America needs talent” argument includes, but only by implication, a call for talented humanities specialists capable of engineering the leveling functions of general ed (206-07). Were the Rebooks authors to make this argument explicitly, they would hazard looking like their great antagonists: propagandists and advertisers (266).

Back to the present. Despite the dominance of “college for all” rhetoric, I think we continue take for granted the idea that “college” is a tiered market of different types and qualities of institutions. I also think we continue to imagine that excellent K-12 education should ideally be equally available for everyone (even though it manifestly is not). Doubtlessly the fact that K-12 education is, for the most part, compulsory in the US has a great deal to do with this. (I wonder what the Carnegie poll results you cite would be if, after being asked whether higher education should be a “right,” respondents were also asked if it should be required?) If “college for all” has not changed these assumptions, then it contains a meritocratic logic within it: the assumption is that everyone will be able to get into and attend some college or another according to their merits; not everyone will be able to get into every college; some BAs will be more equal than others. In the Carnegie poll, 67% of respondents said that funding was the greatest barrier to attending college. Which college, one wonders, did they have in mind? The “best” college to which a student is admitted? Any college whatsoever? It’s unclear to me that for any given student there would be a huge difference, although marketplace intuition says it’s always possible to buy up. My main point is that the question ambiguates the difference. It allows us to imagine that “attending college” equals “attending any college” and simultaneously that it means “attending the best possible college for that student.” The rhetorical shift from “America needs talent” to “college for all” is perhaps best grasped, then, not as a move from meritocracy to equal opportunity, but as a shift in emphasis from the nation’s needs to the individual’s. Both formulations, it seems to me, rely on old-fashioned liberalism’s logic that society and individuals have opposing interests that should be balanced. I think we both regard that logic as powerful, but bogus. This may suggest an avenue for further comment along the lines of pointing out that individual merit is meaningless except in reference to group norms.

Here’s more evidence that the shift from “America needs talent” to “college for all” amounts to no fundamental change. In the press release announcing the Carnegie poll results, Carnegie President Vartan Gregorian finds Redbook rhetoric ready to hand: “We shortchange our nation’s progress and squander our greatest renewable resource–our intellectual capital–if we allow critique of academia or passing partisan squabbling to stifle investment in higher education.” With Jefferson he appeals to “intellectual capital,” and with Jackson, national unity. One could say that Gregorian’s a throwback who preaches to a shrinking choir–I’m not so sure of that–but my point would be that, anyway, he does so under the “college for all banner.”

I know I’m leaving a lot of threads dangling, but indulge me in one more. Bill Gates, interviewed by the Chronicle on the Morrill Act anniversary and at the height of the Sullivan episode , speaks unapologetically about what business leaders want to bring to higher ed: a set of approaches geared to identifying best practices and solving those structural problems affecting large numbers of students. Public enemy number one: completion rates. I’ll go out on limb here and declare that not only am I not against improving completion rates, but also that I think Gates is right to identify this as the kind of issue with which business leaders should be concerned. I acknowledge the problems involved in treating completion as a reliable metric made apparent in here. Nonetheless, “completion rates” gives Gates a way to ask about what Universities are doing to deliver what they say they’ll deliver without telling them what they should deliver (in terms of curriculum, e.g.). Does this Jacksonian emphasis amount to a rejection of funding meritocracy? Not at all. Gates says he funds “change agents” who model the best practices that improve completion rates. There is a lot of room for humanities expertise here, it seems to me. No surrender of clichés would be required. Critique and completion are compatible. What might be required are changes in how the workforce is structured, how the curriculum is imagined, how space is used on campus, etc.

So my answer is that funding for meritocracy is not in jeopardy, but meritocracy may well be depending on where the funding for it ends up coming from. We have not arrived at a new day in which established defenses of general education, talent, and “critique” have lost all traction. What has broken down are the mechanisms conjoining these rhetorics (ideologies?) with the actual practice of humanists, who look most out of touch not in the content of our scholarship (who reads most of it anyway?), but in the institutional configurations we tend to defend. Defend is the right word. Where’s the offense? This Chronicle headline may be relevant.

Mark