Collaboration

Dear John,

I recently got notes from Ralph Berry about our presentation at Florida State. The value we place on “collaboration” was a central topic. Ralph reminded me of the Q&A in which some questioners pointed out that “collaboration” does not have a purely positive connotation. Sometimes “collaborators” are enemies of the cause. There’s a big difference between those who collaborate with “us” and those who collaborate with “them,” but, at least in the fictions that deal with this problem, it’s not always easy to tell who’s who. In Casablanca, for example, Louis collaborates with the Nazis right up to the end when he and Rick begin again, but of course this beautiful new start is possible because he and Rick have been collaborating all along. And although Rick says he sticks his neck out for no one and seems to be quite a loner, he’s clearly an arch-collaborator, forming ad hoc partnerships and knitting them together so that Ilsa and Lazlo can catch their plane. Collaboration entails an idea of the common good and an epistemological uncertainty about it.

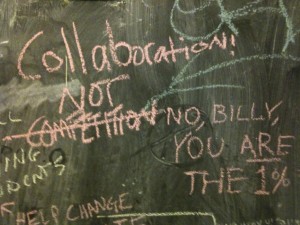

This twofold proposition is encapsulated in the photo we showed during out talk. (I’ve added it here before, but you suggested we table discussion . . . until now!) The image captures a struggle to define the terms of collaboration. Graphic Artist One (Billy) sets collaboration over competition. In denying Billy anonymity, Graphic Artist Two negates his statement by disallowing the standpoint from which he makes it. The idea here is that persons belonging to the 1% have no authority to assert the value collaboration over competition. Such a statement is hypocritical because the 1% benefit from a competitive process that unfairly privileges them above the 99%. Probably there is more going on outside the frame. We are free to imagine the Graphic Artist Two feels an animosity toward Billy that far exceeds, and may be largely unrelated to, their relationships to the distribution of wealth. In any case, it seems that Billy wants to be one of “us,” while Graphic Artist Two insists, no, you are one of “them,” a collaborator with the competitors. This interpretation assumes that “Collaboration!” and “NOT COMPETITION” have the same author. The handwriting looks the same, although the shift to all caps may introduce an ambiguity: a different time of writing or simply a matter of emphasis? The line through “competition” presents a more serious conundrum. Are we to regard it as part of Graphic Artist One’s initial statement–an iconographic negation of competition to underscore the semantic negation of the “not”? Or is this part of Graphic Artist Two’s statement? If the later, we can understand it as a kind of double negative. Graphic Artist Two iconographically invalidates as bad faith Billy’s semantic negation of competition, while leaving the imperative “Collaboration!” untouched. I like this second interpretation. It seems to be of a piece with Graphic Artist Two’s cynicism: a reminder that while collaboration might be valued over competition it cannot be opposed to it, since would-be-collaborators begin from a position in a competitive hierarchy with which they may unwittingly collaborate despite avowals to the contrary. The image-arugment thus encodes the complex proposition that “collaboration” entails an opposition, a “them,” and that the ground for the us-them distinction is inherently unstable. It is easy to break collaborations apart by denying the principle commonality that unites them. It is perhaps equally easy to find alternatively commonalities, grounds for collaboration where none seemed to exist. Which is to say, I suppose, that collaborations exist as they are practiced and not as they are planned or defined.

This twofold proposition is encapsulated in the photo we showed during out talk. (I’ve added it here before, but you suggested we table discussion . . . until now!) The image captures a struggle to define the terms of collaboration. Graphic Artist One (Billy) sets collaboration over competition. In denying Billy anonymity, Graphic Artist Two negates his statement by disallowing the standpoint from which he makes it. The idea here is that persons belonging to the 1% have no authority to assert the value collaboration over competition. Such a statement is hypocritical because the 1% benefit from a competitive process that unfairly privileges them above the 99%. Probably there is more going on outside the frame. We are free to imagine the Graphic Artist Two feels an animosity toward Billy that far exceeds, and may be largely unrelated to, their relationships to the distribution of wealth. In any case, it seems that Billy wants to be one of “us,” while Graphic Artist Two insists, no, you are one of “them,” a collaborator with the competitors. This interpretation assumes that “Collaboration!” and “NOT COMPETITION” have the same author. The handwriting looks the same, although the shift to all caps may introduce an ambiguity: a different time of writing or simply a matter of emphasis? The line through “competition” presents a more serious conundrum. Are we to regard it as part of Graphic Artist One’s initial statement–an iconographic negation of competition to underscore the semantic negation of the “not”? Or is this part of Graphic Artist Two’s statement? If the later, we can understand it as a kind of double negative. Graphic Artist Two iconographically invalidates as bad faith Billy’s semantic negation of competition, while leaving the imperative “Collaboration!” untouched. I like this second interpretation. It seems to be of a piece with Graphic Artist Two’s cynicism: a reminder that while collaboration might be valued over competition it cannot be opposed to it, since would-be-collaborators begin from a position in a competitive hierarchy with which they may unwittingly collaborate despite avowals to the contrary. The image-arugment thus encodes the complex proposition that “collaboration” entails an opposition, a “them,” and that the ground for the us-them distinction is inherently unstable. It is easy to break collaborations apart by denying the principle commonality that unites them. It is perhaps equally easy to find alternatively commonalities, grounds for collaboration where none seemed to exist. Which is to say, I suppose, that collaborations exist as they are practiced and not as they are planned or defined.

According to Ralph, our emphasis on “collaboration” sounded a bit like Billy’s when we made a “them” out of defenders of disciplinary objects. To the extent that these folks are trying to figure out how disciplines work, he pointed out, they could be seen as collaborating with us. He offered Ransom’s “Criticism, Inc.” as a test case. We follow the crowd in presenting Ransom as a mid-century professionalizer who equated English departments with the work of criticism (as opposed to history or appreciation) and the work of criticism with keeping poetry from “being killed by prose.” I continue to find it telling that Ransom defines “criticism” mostly through a set of prohibitions. Be that as it may, I think Ralph’s got a point that no matter how low we estimate Ransom’s approach, it is notably self-conscious in saying what English should be as a professional endeavor. Above all, Ranson’s a reformer:

Professors of literature are learned but not critical men. The professional morale of this part of the university staff is evidently low. It is as if, with conscious or unconscious cunning, they had appropriated every avenue of escape from their responsibility which was decent and official; so that it is easy for one of them without public reproach to spend a lifetime in compiling the data of literature and yet rarely or never commit himself to a literary judgment.

Nevertheless it is from the professors of literature, in this country the professors of English for the most part, that I should hope eventually for the erection of intelligent standards of criticism. It is their business.

Do we collaborate with Ransom in trying to figure out 1) what it means to be an English professor and 2) how this could be made more satisfying work? I think we might when we use him to call attention to assumptions that continue to inform the practice of the discipline, even if few current practitioners would explicitly avow the whole “Criticism, Inc.” package.

Mark